Review by Prof. Dr. phil. Makiko Hamaguchi-Klenner

The NATSU DANCE (NATSU ZORA DANCE 夏空ダンス) focuses on the relationship between a father and his daughter. The father, portrayed by the director himself, strives to revitalize his hometown in Southern Japan after it’s been ravaged by earthquake and flood. However, he’s disheartened to learn that his talented daughter, along with many others in the town, desires to leave and seek a better life in larger cities.

The film paints a picture of a traditional Japanese family dynamic, where the mother manages household responsibilities while the father holds authority in decision-making. The protagonist, NATSU (Summer), a skilled dancer, has injected vitality into the desolate town but now yearns to depart. In the past, the father might have insisted she stay.

Yet, in contemporary Japan, many housewives earn their own income, even through part-time work. Their voices carry weight in family matters, and husbands have come to value not just their wives but also their daughters, who deserve promising futures. After reflection, the father not only permits NATSU to pursue dance lessons in Tokyo but also welcomes her return should her endeavors not thrive.

In Japanese, “NATSU ZORA DANCE” translates to “Summer Sky Dance”. “空” means “sky” and implies that the dances took place in open air, while “夏” (Natsu) refers to both her name and the season during which they danced. “ダンス” (dannsu) represents the English word “dance”, and “空” denotes sky.

“The Last Party” focuses on the relationship between sisters, delving into the intricate psychological dynamics that require time to unravel. Despite their mutual love, differences in mentality, preferences, and lingering competitive feelings from childhood hinder their ability to openly express affection. It’s a journey where they must each live their lives and experience loss before they can authentically reveal their true emotions to one another.

The “Katvoman” focuses on the relationship between a mother and her son, with domestic violence (DV) as its central theme. While the father’s presence is acknowledged, his role in the film is relatively minor. Domestic violence, whether physical or verbal, remains a prevalentissue worldwide, albeit more prevalent in certain regions. Viewers may question why this cycle persists. The intimate bond between mother and son serves as a key insight. The mask she wears to conceal her scars becomes symbolic of the secret she keeps from her son. Perhaps she should have revealed her scars, explaining that conflicts between parents are inevitable, and he shouldn’t take sides without understanding both perspectives. Importantly, he should never resort to violence against his future spouse, but instead, respect her as an individual. Failure to impart such lessons could perpetuate psychological harm, leading the young boy to replicate his father’s mistakes.

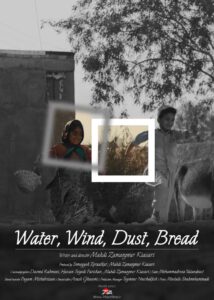

“Water, Wind, Dust, Bread” was challenging to discern the central theme of this movie as it addressed numerous issues: poverty, limited educational opportunities, the affection between a boy and a girl, and the boy’s disabilities, among others. However, viewed through the lens of women’s emancipation, the film primarily revolves around the relationship between a privileged boy and a less fortunate girl. The girl, unable to attend school due to a lack of birth certification, forms a close friendship with the boy and assists him with daily farm chores. By the film’s conclusion, it seems improbable that the girl will ever attain the same privileges as her counterparts in more developed areas. Despite the boy’s kindness, he does not teach her to read or write, preferring independence and refusing her assistance. This behavior hints at a potential future where he may become a dominant husband, despite his kindness. The discrepancy between genders appears especially pronounced in impoverished regions of the world.

Prof. Dr. phil. Makiko Hamaguchi-Klenner, Political Sciences, Born in Tokyo in 1949, spent her childhood in California before delving into Chinese Affairs through studies in Tokyo and Singapore from 1969 to 1974. With a passion for East Asian Politics, she shared her expertise as a lecturer at Ruhr-Universität Bochum from 1991 to 2015. Alongside her academic career, she actively engaged in global discourse, attending World Women Congresses in Prague and Moscow, contributing to discussions on gender equality and societal progress. A staunch advocate for gender equality, she brought a unique perspective to her academic and activist endeavors. Makiko’s dedication to bridging cultural divides and fostering dialogue continues to inspire positive change worldwide.

“The Last Party”, Italy, screenplay and directed by Matteo Damiani, is a enchanting film about two sisters who encounter each other anew in their old age.

“The Last Party”, Italy, screenplay and directed by Matteo Damiani, is a enchanting film about two sisters who encounter each other anew in their old age.

“Water.Wind.Dust.Bread”, Iran, screenplay and directed by Mehdi Zamanpour Kiasri, which, as a documentary, equally engages with the fate of a boy with physical disabilities and girls in the Afghan border region who are unable to attend school due to political circumstances. Four films, four such different realities of girls and women – and all are present. A rich and enduring evening at the Superraum.

“Water.Wind.Dust.Bread”, Iran, screenplay and directed by Mehdi Zamanpour Kiasri, which, as a documentary, equally engages with the fate of a boy with physical disabilities and girls in the Afghan border region who are unable to attend school due to political circumstances. Four films, four such different realities of girls and women – and all are present. A rich and enduring evening at the Superraum. Born in Munich, Professor Dr. Irmgard Merkt, affiliated with TU Dortmund, embarked on her journey into German music education following her studies in opera singing. Transitioning to music education for grammar schools, she earned her doctorate in 1983 with a pione

Born in Munich, Professor Dr. Irmgard Merkt, affiliated with TU Dortmund, embarked on her journey into German music education following her studies in opera singing. Transitioning to music education for grammar schools, she earned her doctorate in 1983 with a pione