Cheryl De Ciantis in her own words:

I have loved to draw since childhood; and any medium I use—oil painting, mixed media drawing and sculpture, or anything that comes to hand, is a means of exploration: into an idea, into a story, into a face—and all faces are marvelous. Recently I have returned to one of my first loves, portraiture, of both real and of mythical beings. I am beyond grateful for all the examples and influences of friends—fellow artists, architects, historians, researchers, poets, filmmakers, theater artists and simply exceptional people—in developing the confidence to spend a life doing what energizes me. I also endeavor to use the wisdoms I have received in mentoring and teaching younger people, and receive learning from them in turn.

My interest in human systems led me to become a Senior Faculty member of the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), an international not-for-profit organizational leadership research and training institution, where I have spent a large part of my public career. As Director of CCL’s Brussels campus, and, more recently, co-founder of Kairios, I have co-designed and delivered creative leadership development programs for dozens of organizations in the U.S., Canada, and Europe; and creative, values-based coaching to hundreds of people. I have had the opportunity to publish articles and three books on my researches; and I am co-creator of the Kairios Values Perspectives online survey.

I earned my B.A. at UCLA in Art History and Connoisseurship, and a Ph.D. in Mythological Studies and Depth Psychology from Pacifica Graduate Institute, which houses the Joseph Campbell Library and archive. A significant part of my research is the study of myths found in cultures worldwide that celebrate the mysteries of physical embodiment and the human desire to live a good life, create, and come to peaceful terms with the ultimate mystery, death.

I live near Tucson, at the foot of the Catalina Mountains in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona, with my husband and creative partner, artist and educator Kenton Hyatt.

The Interview

Mahmood Karimi Hakak: You’ve been drawing portraits of women since 2015, nearly 7 years, and you’ve created more than 100 of them. What got you started? What does it mean to you? Why do you do it?

Cheryl DeCiantis: I have always loved portraiture and have been able to make a likeness; not always perfectly, but it seems to be something in my brain, just perhaps as abstraction comes naturally to some artists who create openings for meaning through their receptivity to the possibilities of pure color and marks. I initially got started partly because I was seeing a proliferation of images of women, and we were looking forward excitedly to our first female U.S. president. I started reflecting on all the women who have inspired me and why. The images I was seeing at that time were most often by artists who did not prioritize the making of a true likeness, who were probably using image to make a mark to direct our attention: “Look, here is someone significant, someone you need to know about.” I love that; but I also feel strongly that making a likeness in which the person would hopefully recognize something of herself is also extremely important. One of my most respected teachers, Betty Edwards, warned us, “Be careful what you choose to draw, you’ll fall in love with it.” I absolutely find that to be true. I try to feel my way into the woman’s spirit—in doing that I must give credit to my life partner, the painter Kenton Hyatt, whose paintings and photographs, though never sentimental, are very emotionally evocative, which is of first importance to him, and he stays true to it in his work. Inevitably some of the portraits say more about me, and though lives can take strange turns and we can never know the deepest heart of someone else, I will not make a portrait of someone I cannot respect. One of my latest portraits is of Liz Cheney, the American conservative politician who has put her career on the line to speak truth and stop the takeover of her party—and our now-fragile democracy—by Trump.

MKH: How do you choose whom to draw? (and why women, not men?)

CD: I want to draw women because I am a woman and I needed, and need, to see images of women. It’s become very popular and that’s fantastic, because we all need to see images of inspiring, powerful, fascinating women. I do wish that real men were more celebrated and thanked, men who are doing the right thing, and there are many, many of them. I have granddaughters and want them to know about women they might not encounter these days, people who inspired me. I am interested in the lives and accomplishments of artists of all kinds, women who have advanced the sciences, women who have served society, women who have awakened our imagination; serious women, wild women. The gift of the internet is that women who were formerly invisible can now be found and celebrated.

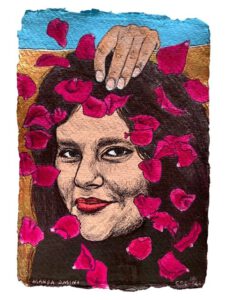

Mahsa Amini, age 22, was arrested on September 13, 2022 in Tehran for “wearing inappropriate hijab” by the morality police responsible for enforcing the dress code of the Islamic Republic. As reported thanks to female journalists now imprisoned, she was severely beaten and died in police custody three days later. Her death has sparked some of the largest protests in Iran since 1979.

MKH: Why is it important to get a good likeness of the women you draw?

CD: The images that are out there can seem very cartoonish to me. I think they are valuable, and I recognize a lot of artists have been putting out images intended for young girls, which is great. But I also think that a good likeness gives the person the dignity they deserve, and it makes us want to look more closely at the woman as a person. I try to get as close as I can to getting what seems to me to be the likeness. Sometimes I do better; sometimes I feel perhaps I’ve gotten the spirit. For me, a good likeness means something of the essence is there. The woman comes across as real.

I know almost none of the women I’ve drawn, and many of them are no longer living. I collect as many photos as I can off the internet, so that I can not only choose the one that I want to make a drawing of, but to sort of triangulate the available information. How does she look from a different angle? In different light? With different expressions? At different ages? In the case of some women I want to commemorate their youth; others feel to me to be powerful elders no matter what they did earlier in life, and we need positive images of elders who have made something of their lives. It’s significant to me whether a woman is shown smiling—sometimes, as was the case with Sandra Bland, the young woman who died in Texas in police custody in 2015, a woman’s smile can be politically manipulated. She had a great, goofy smile, which was used by racist trolls to discredit her, to persuade people not to take her seriously, in order to minimize the awful impact of her death at age 28. It was important to me to find an image of her looking serious, which she was. She was on her way into a career of social service and advocacy, helping others, when her life was cut short.

MKH: Why have you chosen to make portraits of Iranian women?

CD: I have always been aware that Iranian women have been forced to endure unthinkable repression under the four decades of the Islamic Republic. I was so struck when I heard about the protests sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini, and that women were in the streets, burning hijabs and demanding the end to the rule. immediately wanted to know what was happening, to find out. It’s so hard to get news of important events in other countries. Here, we are still so insulated, and I also know many of us are numbed by the trauma of Trump and the serious threat of fascism in this country. We are so traumatized. So, seeing the news of protests I was galvanized—and you raised my awareness in this as you have in the past; because of you I have always a vivid sense of the beauty and depth of Persian culture. I have always felt sympathy for Iranians left in the wake of a heroic overthrow of the shah’s government that was propped up by the West, being overtaken by the religious fanatical men, and women crushed. Your recent writings have helped me to see the historical currents—I’m grateful that both of us are “old”—it gives a perspective that is so different from what it was in youth. It’s not that we are not still idealistic—we are also now realistic, and have seen an arc of history, and can see what may be ahead. It’s not good news.

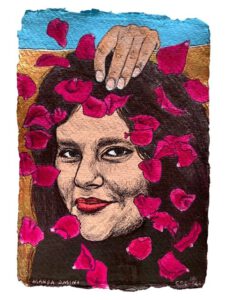

Sarina Esmailzadeh, age 16, severely beaten on the head by security police September 23 in Karaj. They claimed that she committed suicide by jumping from a roof, and her family was pressured to stay silent. In a recent video post she said, “Nothing feels better than freedom.” In her last video on Telegram, she said, “My homeland feels like being in exile.”

The repression of women is as old as history, which tells us it’s way older than that. Most of us internalize it—our mothers teach us—and worst of all, too many women are actively complicit. It seems like half the new politicians in this country are women who support the power grab by the GOP. That to me is sickening. I feel rage toward women who “collaborate.” That’s one reason why I feel so passionately that the women who resist need to be recognized, supported, their names and struggles kept at the forefront of our fickle attention spans.

I have drawn falling rose petals around the faces of women who have been killed while protesting the killing of Mahsa Amini. To me, the petals signify the hope and the passion of each of these women, and the choices they made that led each to sacrificing themselves. We must honor them and keep their names alive. The colors of the petals are a little different for each because each was an individual with her own dreams and convictions. I hope not to keep drawing rose petals.

Women in Iran, for example the sister of Hadis Najafi who was shot protesting the death of Mahsa Amini, have started to say, “We are no longer afraid.” It’s terrifying to hear this, but I so hope that they may prevail, after so many prior attempts. You have pointed out that this is different, it’s a protest led by women, and I’ve heard that people from all classes are rising in indignation against the savage violence of the Morality Police. Permit me to say that the women members of this cadre are the worst of the worst. I have no pity for them, only rage. I will not draw women I could not sympathize with and I will not draw the women I deplore, whether they are power grabbers themselves, or simply cowardly. Women are terrifically strong, as you’ve made a point of saying, and I appreciate, and we are stronger in solidarity.

MKH: What do you want other people to get from these images?

CD: I want people to feel these women as real, as unique, as powerful, as worthy of our respect and attention. I want people to be curious about them, to find out about them, especially if one or another image resonates with them in a special way. I want them to be drawn in by the likeness; some people will respond to certain images, others will feel some connection with entirely different ones. That’s one reason I simply keep going. The more I look, the more I find. I hope that for people who see these, especially as a body, a growing body, of work and devotion, that they will be inspired to think of who inspires them, and why. I want them to think of themselves as capable of being in the world in a way that inspires others, to see themselves as powerful. How often men, and women, have said, “Women have not made history, they have not contributed like men.” That’s total bullshit. Look and you’ll find. One thing I love about the chaotic internet is that the more you look for images of women who have made a difference, the more you will find. The more women, especially young women, see women as capable of making a difference, in every field of human endeavor, the more they become capable of seeing that potential in themselves.

MKH: Why are these images important for you, now?

CD: We are hearing of demonstrations, and hearing about the courage of demonstrators even though the authority has curtailed the internet. Their lives, their names, are important to me, and they are important for all of us to know. A woman friend of mine here in the US, someone I respect very greatly, said she was aware of demonstrations but said, “I don’t know their names.” If I do this work and give her and other people names and faces, then more of us know what is happening. The work depends on others, to share what information we can find, to research, and to get the information out there however we are able. I can contribute artistically, to give a name, and to the best of my ability to give a face to the women who are being cut down but also to those who are persisting in the face of violence and death. We owe them our attention—as we owe the men standing beside them and being cut down, and my hope is that putting their faces out there will get more people concerned, to call out their humanity. And we need to see the courage they are showing—we all need courage now, especially women, to stop the wrongness. There is wrongness in Iran, there is wrongness in the U.S. and it needs to be stopped.